Researchers discover long-sought mechanism behind worst cases of a common blood disorder

G6PD deficiency affects about 400M people worldwide and can pose serious health risks. Uncovering the causes of the most severe cases could finally lead to treatments.

With a name like glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, one would think it is a rare and obscure medical condition, but that’s far from the truth. Roughly 400 million people worldwide live with potential of blood disorders due to the enzyme deficiency. While some people are asymptomatic, others suffer from jaundice, ruptured red blood cells and, in the worst cases, kidney failure.

Now, a team led by researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory has uncovered the elusive mechanism behind the most severe cases of the disease: a broken chain of amino acids that warps the shape of the condition’s namesake protein, G6PD. The team, led by SLAC Professor Soichi Wakatsuki, report their findings January 18th in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

An essential enzyme

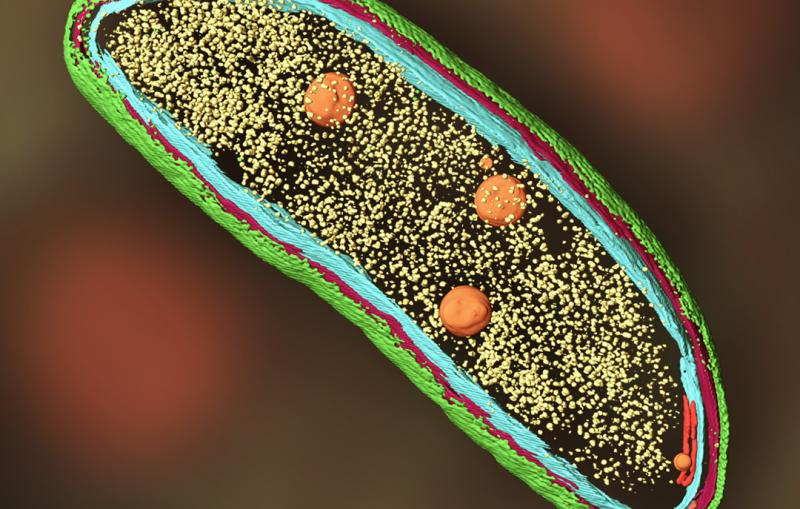

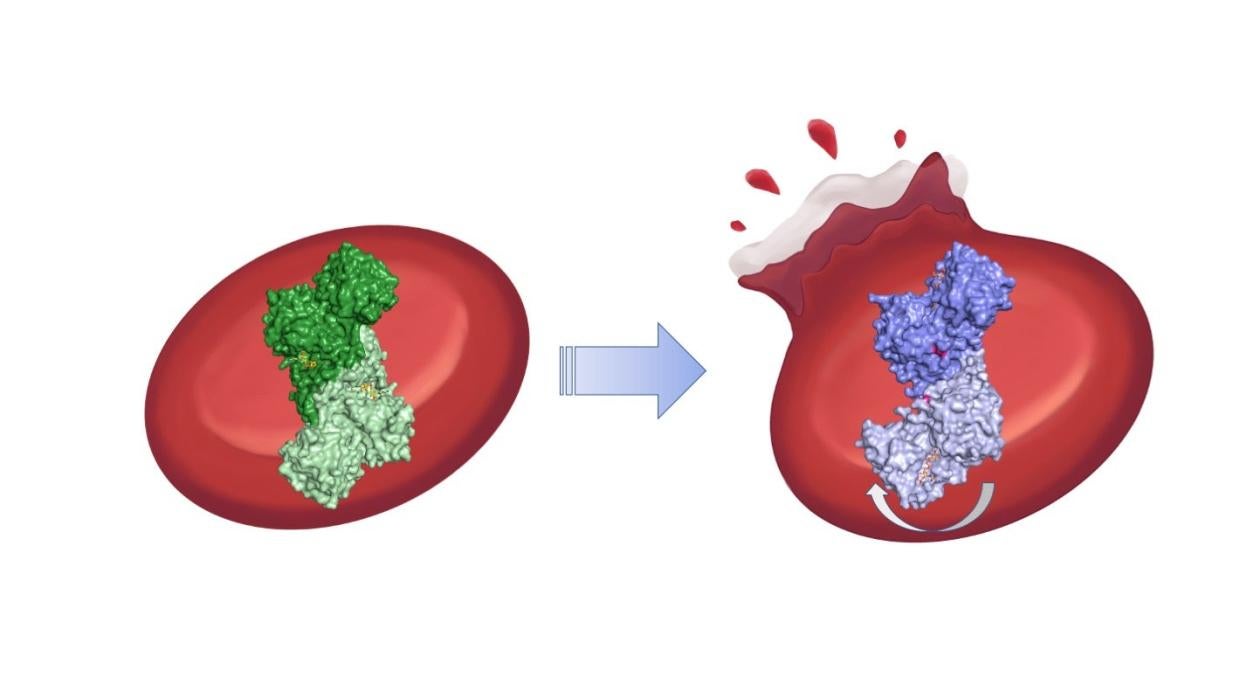

G6PD’s role in our health is hard to overstate. In red blood cells, which deliver oxygen to other cells, the enzyme helps remove more chemically reactive and potentially harmful oxygen molecules, such as hydrogen peroxide, and convert them to water and other more inert byproducts. If the G6PD protein isn’t working properly, red blood cells also stop working properly and can, in the worst cases, rupture.

“It’s quite an important enzyme in our bodies,” Wakatsuki said.

Still, doctors have mostly been at a loss to treat the disease, especially in the most severe cases, known as Class I. “At the moment the treatment for these patients is blood transfusions,” said Stanford professor Daria Mochly-Rosen, a senior author on the new study.

Medical researchers have known for decades that upwards of 190 different mutations can lead to some forms of G6PD deficiency, and they also worked out the structure of ordinary G6PD in various forms decades ago. Mochly-Rosen and colleagues have also made strides in identifying drugs that may treat some less-severe forms of the disease, known as Class II and III.

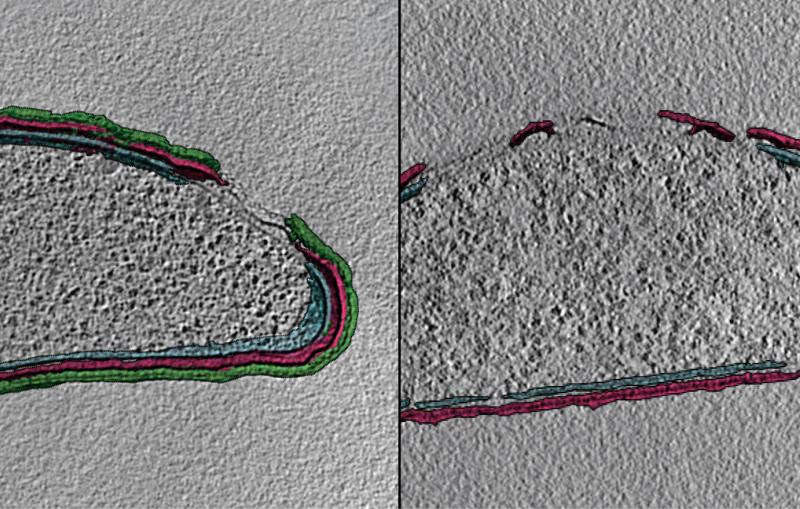

Unfortunately, those drugs do not work for Class I cases, which have proved especially confusing. Most of the mutations that lead to the most severe symptoms were known to occur in areas far away from the active site where it binds to substrate molecules for its enzyme reactions – the usual spot where such mutations would be thought to cause problems.

A bend in the road

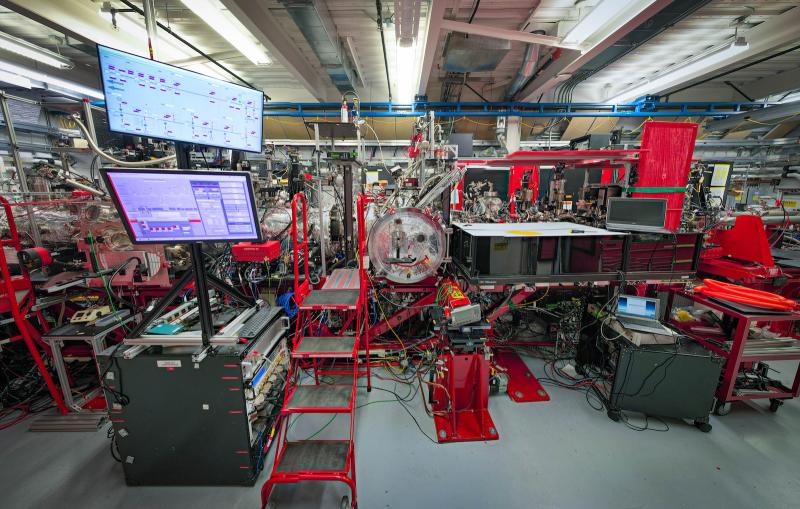

To better understand what was going on, Wakatsuki and colleagues from SLAC, Stanford University, the University of Tsukuba and the University de Concepción – along with a group of Stanford undergraduates and local high school students – started with X-ray crystallography studies of four forms of G6PD associated with the worst G6PD-deficiency symptoms, conducted at Structural Molecular Biology beamlines at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s Advanced Light Source and Argonne National Laboratory’s Advanced Photon Source.

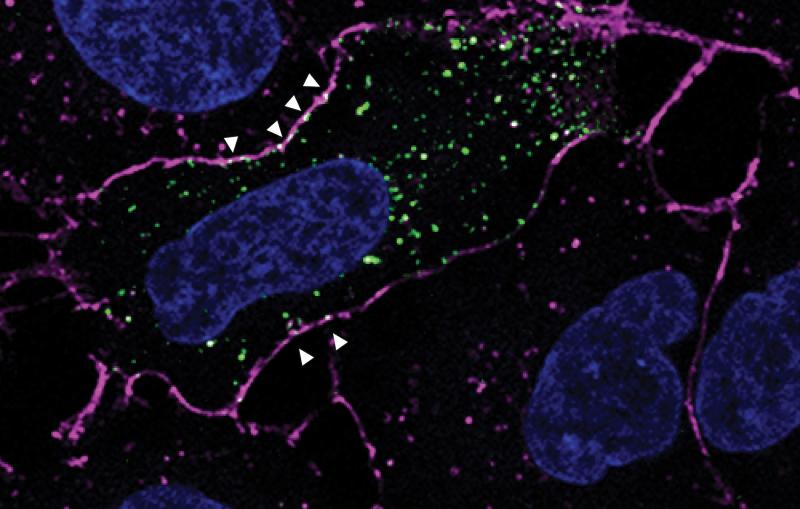

The team found that even though the mutations are far from G6PD’s active site, they break up connections in a chain of amino acids that help stabilize the protein. That has a kind of domino effect on the whole protein molecule: It bends awkwardly, and a molecular arm that should help molecules bind to G6PD’s active site instead wobbles unpredictably around. The team confirmed aspects of those results with a mixture of other techniques, including small angle X-ray scattering at Beam Line 4-2 at SSRL, computer simulations and cryogenic electron microscopy performed at the Stanford-SLAC Cryo-EM Center.

The results show for the first time how the most severe cases of G6PD deficiency work at the molecular level and could help researchers design new drugs to treat the disease.

“It’s been some time we’ve been working on this,” Wakatsuki said. “There’s no cure so far, but this could pave the way for new therapeutics.”

Mochly-Rosen agreed. “You can start to imagine what kind of drug you need,” she said. “With Class I, we were stuck until we found this clue.”

The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. SSRL, ALS and APS are DOE Office of Science user facilities. The Stanford-SLAC Cryo-EM Center is supported by the National Institutes of Health. The Structural Molecular Biology Program at SSRL is supported by the DOE Office of Science and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Citation: Naoki Horikoshi et al., 19 January 2020, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (10.1073/pnas.2022790118)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.